What Should Residential Users Consider When Installing Solar Energy

time:2023-08-24 09:26:23 Views:0 author:Jinan Freakin Power Ltd.

The battery-powered life

Solar power is seen as one key to the renewable energy future, but rooftop solar has one glaring problem: It generates too much power when it isn’t needed, and too little when the demand for power is straining the grid. To tackle that issue, NEM 3.0 provides a strong incentive to add high-capacity batteries to rooftop systems to store the excess power generated during the daytime. You might think of a battery as a cool thing to have during a blackout, and indeed it is. But it’s also a way to time-shift solar power from day to night. That way, if you’re running your clothes dryer at 9 p.m., you won’t have to pay your utility’s peak prices. And if you have extra power, you can sell it to the grid when wholesale prices are much higher — and the utilities really need the extra capacity. Batteries such as the Tesla Powerwall cost notably less than a Tesla, but a heck of a lot more than a pack of Energizer AAs. Prices for the battery start around $7,500, not counting the 30% federal tax credit. According to EnergySage, a Boston-based online marketplace for clean-energy technology, a fully installed home storage rig will cost $10,000 to $20,000.

Before you rattle off all the other wonderful things you could do with $10,000 to $20,000, consider this: According to the PUC, adding a battery to your rooftop solar system will boost your savings by more than a third on average, from about $100 a month to at least $136. As a result, the commission estimated that it would take a wee bit less time for a solar-plus-battery system to pay for itself than a panels-only system would — for Edison customers, about six weeks less. (For its part, Edison says the payback period for a rooftop system with a battery would be 6.6 years, which Smith of Solar Optimum described as a “best-case scenario.”) Part of the cost of adding a battery is the extra equipment needed to ensure your home can run just on battery power in a lengthy blackout. If you’re willing to dispense with backup power and use the battery just to cut your utility bill, Smith said, you can cut your battery costs by 20% or more. To ease the sticker shock, the investor-owned utilities offer rebates for home battery systems connected to the grid. Edison is currently offering 15 cents per watt-hour of storage capacity, which, for a 10-kilowatt-hour battery, translates to $1,500. (Southern California Gas offers 20 cents.) For low-income households and homeowners in areas with high fire risk or multiple blackouts, the incentive rises to 85 cents, enough to cover most of the cost of a battery. But the rebates decline as more people sign up for them. Those subsidies originally came from ratepayers. Last year the state Legislature approved $270 million in battery subsidies, but Gov. Gavin Newsom’s latest budget proposal cuts that funding in the coming fiscal year. Instead, the budget includes $630 million in subsidies for solar panels and batteries for low-income households, the details of which are still being worked out.

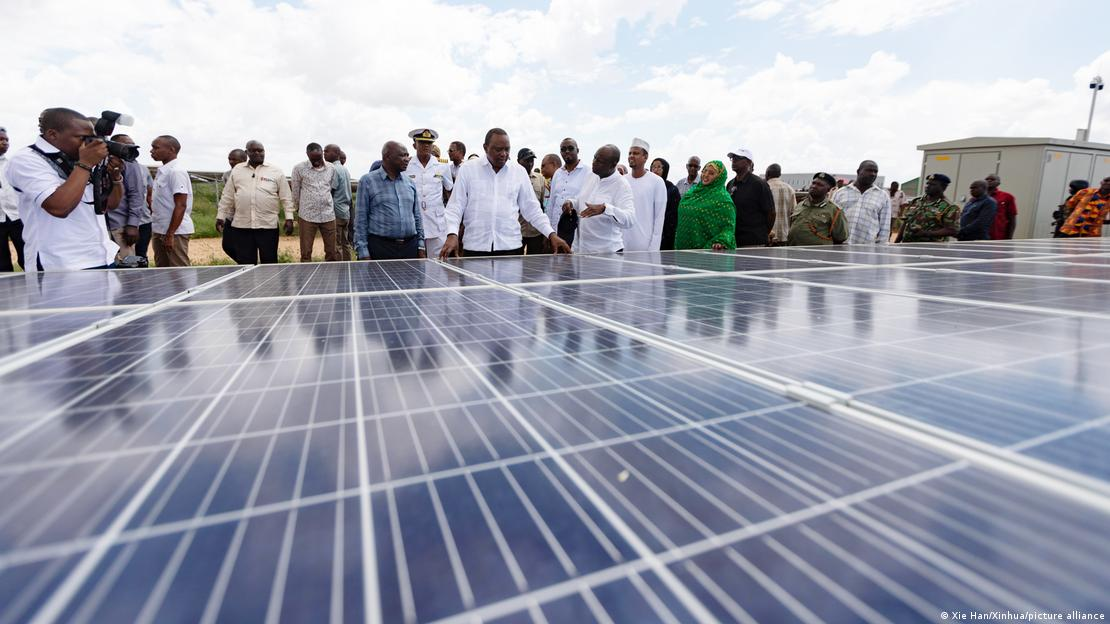

How much power your roof can provide

Before going any further, ask yourself why you’re interested in solar panels. If the survival of the planet is your sole concern, feel free to skip ahead to the next section. You’re committed to going solar; all that’s left to be decided is how to pay for it. For most people, however, the No. 1 goal is to rein in their growing electricity bill, said Vikram Aggarwal, founder and chief executive of EnergySage. Climate and the environment are definitely on people’s minds, he said, but they “don’t usually drive the purchasing decision.”

To get a rough idea of how much you can save by going solar, start by looking at your utility bills to see how much power you’ve been using over the last year and how much you’ve paid for it. Then — and this is the part you’ll probably need some help with — calculate how much electricity your panels could generate. Your roof’s generating capacity is a function of how much sunlight it receives and how much space it has for solar panels, especially on its southern and western exposures (the first sees the most sunlight; the second can generate power late in the afternoon when electricity rates are higher). One other factor is the wattage level of your panels, which can range from 250 watts to 400 watts. You can try to run the numbers yourself — see, for example, the DIY guidance from EnergySage — or you can invite a few solar-power installers to pay a visit and give you an estimate. There are also websites aplenty that can help you estimate your roof’s generating capacity, most of which demand your contact information so they can refer you to solar salespeople. One that doesn’t is Google’s Project Sunroof, which offers an estimate of your power-generating ability and your potential savings.